Working with Orbion showed how translation, not expertise, can unlock deep-tech storytelling and help founders communicate complex science clearly.

Note: The following contributions are personal impulses from Max Eckel. They represent individual reflections and are intended to stimulate discussion and further thought.

Some startups you understand in one minute. Orbion was not one of them. When I first started coaching the Orbion team, co-founded by WHU alum Aniruddh Goteti alongside Çağlar Bozkurt during the WHU Accelerator, I had the same experience over and over again: I thought I understood what they were building. And then I realised… no, not really.

Orbion works on a deeply technical problem in drug discovery: predicting the functional effects of genetic mutations at massive scale. If you’re a pharma researcher or computational biologist, this sentence makes perfect sense. I know for a fact that their ideal customer profile understands them immediately. I didn’t. But the team never used that against me. They were incredibly patient about it.

Early on, I remember asking a question that probably gave away how little I knew: Isn’t DeepMind’s AlphaFold already “solving this?” It doesn’t. AlphaFold predicts the shape of a protein. Orbion predicts the consequences of messing with it — which turns out to be a very different beast.

Another moment: “Why are two computer scientists working on this?” Only after a long explanation did it click for me that the real bottleneck isn’t biology but computation: the combinatorial explosion of mutations you need to model and understand. Suddenly it became obvious why two founders with deep modelling and systems experience would tackle this problem. Again, patient explanation. Again, another layer of understanding. After each session, I walked away thinking, “Okay, now I can finally tell their story.” And then the next session would reveal another piece I had completely missed.

Looking back, this is probably the quiet value someone like me can bring to a deep-tech team: not expertise, but translation. You keep asking questions until the story works for someone outside the inner circle — which is exactly the group they eventually need to convince.

Because in the end, customers don’t just buy the science. They buy a story they can act on: clearer prioritisation, saved experiments, better decisions. In Orbion’s case, one practical example is prioritising which genetic mutations are worth validating in the wet lab before investing expensive time and resources. Their models help researchers understand where the signal is strongest. But founders rarely have the time to sit down and turn all of this complexity into a narrative. You need a forcing function: a pitch, a deadline, any moment where clarity becomes urgent.

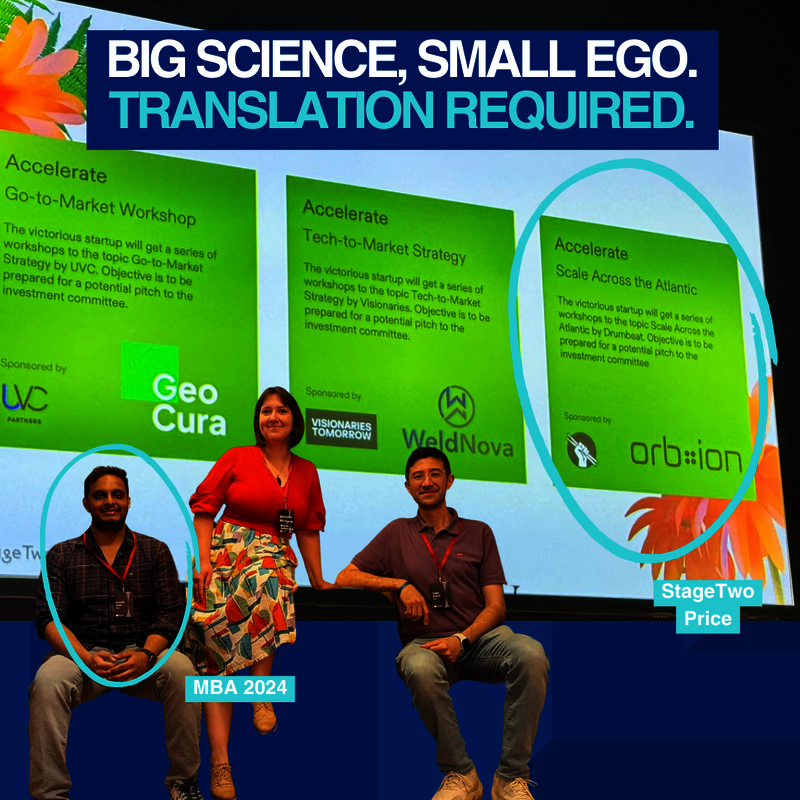

For Orbion, that moment was Stage Two, Europe’s largest university startup competition. They represented WHU there, and they won a prize — convincing one of the prize giver who saw what made them special. I’m genuinely happy about that. Not because of the trophy, but because I watched them wrestle their science into a narrative the rest of us can follow. It’s a small miracle when that bridge appears between the deeply technical and the rest of the world.

Orbion is working on something with the potential to impact millions of lives. But what impressed me most wasn’t just the science: it was their willingness to explain, refine, explain again, and let me ask all the questions their customers never would.

If deep-tech founders ever wonder what a generalist coach (or a pure business co-founder) is good for, maybe it’s just this: being the first person who doesn’t get it, and refusing to fake it.

Why this matters for WHU

People sometimes assume a business school ecosystem can’t support deep-tech. But that’s exactly why environments like WHU work: the forcing functions, the coaching moments, the pressure to make sense of something complex. Scientists often have the truth. What they need is the translation.

And increasingly, WHU’s entrepreneurial ecosystem attracts founders who want exactly that — a place where technical ambition meets a community capable of shaping a story around it. For deep-tech founders looking for business co-founders or a structured pathway into entrepreneurship, the WHU Cofounding Program is one of the simplest entry points.

This is shown in a recent study by Technical University Munich, which showed that between 2014 and 2024, WHU has produced the most DeepTech startups per 1,000 students and achieved spot 9 in Germany in absolute numbers.